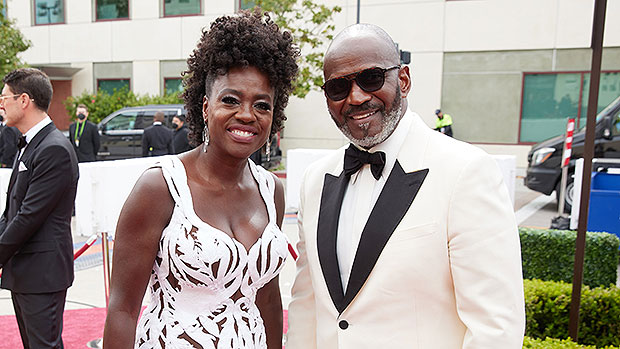

“I loved that Julius always seemed to be very protective of Viola, but not in a way that looked problematic,” King told me. The two would run into each other here and there during awards season, and with Tennon often appearing alongside Davis at various Hollywood events, King got to know him better too. At that event, Davis explained, after cocktails and dinner, “The media leaves, and then we just let loose shoes come off, and makeup is wiped off.” That’s when their friendship began. Years ago, King met Davis at Alfre Woodard’s annual Oscars Sistahs Soirée, which celebrates women of color in Hollywood. Looking both chic and practical in a utilitarian black jumpsuit and head wrap, paired with black Gucci ankle boots embossed with crystals, King was joined by Davis, the undisputed star of last year’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, as well as Davis’s husband, Julius Tennon, an actor and a producer, and their 10-year-old daughter, Genesis. The location for the W shoot was the West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles, which was a hot spot of sorts for Black celebrities like Little Richard and Hattie McDaniel in the 1940s and ’50s. “I didn’t really know why then, but I know now.” “As an actor, I was paying attention and not really knowing why I was paying attention-why I would stay behind, why I would be on set when it wasn’t even my scene,” she said. King can’t pinpoint the exact moment she realized she was a director, but said that in some ways she felt like she had prepared for this moment in her career throughout her entire life. In King’s take, just months before both Malcolm X and Cooke would be killed, the men discuss the topics of colorism and economic freedom for Black Americans, disagree on the ways their unique, individual talents should intersect with their social responsibility as public figures, and wrangle with Malcolm X and Ali’s tricky relationship with the Nation of Islam. Her feature directorial debut, One Night in Miami., based on Kemp Powers’s play of the same name, is a fictionalized account of the real night in February 1964 that civil rights leader Malcolm X, championship heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay), NFL fullback Jim Brown, and soul musician Sam Cooke spent together. In the past decade, her work as a director, initially on episodes of Scandal and Insecure, opened up new avenues for her as a storyteller who edges all of us closer to a clearer understanding of what it’s like to be Black in America.

Along the way, she picked up numerous acting awards: four Emmys (two for American Crime, and one each for Seven Seconds and Watchmen), a Golden Globe, and an Oscar (both for If Beale Street Could Talk). King started out playing a rebellious teen on the 1980s sitcom 227, snagged supporting roles in early-’90s John Singleton films such as Boyz n the Hood and Poetic Justice, and returned to television in the aughts in The Boondocks and Southland. “I don’t think any of us are particularly happy with the state of America, but we still embrace the fact that we are Black Americans, even with all of the things that have happened in history,” King told me. With her timeless appeal, Davis embodies King’s idea of what she terms Black Americana. King began crafting the story months ago by watching old interviews of her friend Davis, in which she could hear “the pain as well as the beauty in the bruises” in her delivery. That was director Regina King’s intention when she orchestrated, with the photographer Andre D. Instead, we see a classical portrait of Black American life. The fact that the star of these photos is the Oscar, Emmy, and Golden Globe–winning actress Viola Davis almost doesn’t register. You can almost hear the sounds of DeBarge or Maze featuring Frankie Beverly-the quintessential track list for any Black family’s reunion, cookout, or lazy weekend afternoon. It could be Los Angeles, Detroit, or New York. That’s where this family of three finds itself, in the backyard of a modest American home.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)